The boundless freedom of selfing less 🪞

On selfing, personhood, and the joy of selflessness. (The Art of Emptiness, Part 2)

It’s time to talk about your self.

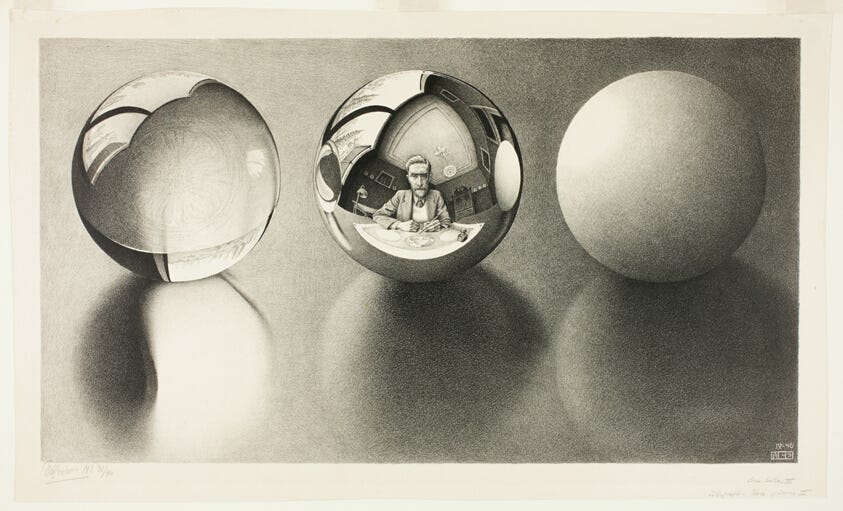

Did you ever notice how frequently your self casts its shadow? Look closely and the self is everywhere. It is for your self that you seek out pleasure and push away pain. If you find yourself being a little too selfish, you address the problem by saying you need to work … on your self.

If we’re honest, however, we find that any way we frame our self—positively or negatively—is a limitation. Our sense of self is a voice in our head constantly whispering: You’re like this. You’re not like this. You can’t be like that. The self-improvement project is doomed to fail from the beginning, because the idea of improvement and the idea of a fixed, limited self are incompatible.

This is not an essay about self-improvement. It’s about selflessness.

In Part 1 of The Art of Emptiness, I introduced the idea that our minds fabricate perception, much like a wobbly table constructed by a friend. This fabrication isn’t necessarily a problem unless it causes dissatisfaction. If it does, though, we can perceive a phenomenon’s emptiness (its lack of permanent, independent existence) in order to unfabricate it.

In this essay, I want to suggest that your sense of self is one such fabrication. That, in countless moments throughout each day, you are constructing a shifting sense of self through a process I refer to as selfing.

Together, I want to explore how and why we construct our sense of self. I want to inquire whether that sense of self maps onto something solid and tangible, or something more slippery and nebulous. And if so, might that actually be good news? What if freedom, well-being, and genuine compassion do not actually come from selfing more?

What if they come from selfing less?

How the sense of self is fabricated

Let me make a (potentially obvious) observation: You have never seen, heard, or touched a self. The self is a concept, and selfing happens when we conceptualize away from our direct experience.

This conceptualization happens through a predictable sequence of steps in which we come into contact with something and come to identify with it.1 The sequence goes like this:

contact • feeling • craving • clinging • becoming • birth • death

Here’s an example. Imagine you’re deeply absorbed in a walk through the woods when you come face to face with a beautiful rainbow (contact). You appreciate it momentarily (feeling), and then a thought strikes you—How many likes could this get on social media? (Craving.) You snap the picture (becoming) and upload it (birth), but then your cell signal cuts out. For the rest of the walk, your mind is consumed with thoughts about how well your post might be doing (clinging). When cell signal returns and you open your phone, a complete absence of notifications puts to rest your fantasy of immense popularity (death). It’s only a matter of time before you make contact with something new and give birth to a new sense of self.

In case it isn’t clear, death doesn’t describe a literal death, but rather the death of an identity. We could describe selfing as a cycle of rebirth—not of the body, but of an identity. In each cycle of selfing, an identity is born, sustained through grasping (craving, aversion, or clinging), and eventually dies. The cycle repeats.

Let’s deepen our understanding by making a couple of further observations about the selfing process.

Grasping creates sense of self. This is a subtle, but significant point. ‘I’ didn’t grasp at social media likes—rather, the grasping at likes created the sense of there being an ‘I.’ This flips ordinary perception on its head. The self is not the agent behind action; the sense of self is the product of action.

Selfing is separation. Before the selfing began, there was only absorption, or flow. Selfing separates subject (‘I’) from object (woods) and inhibits access to direct experience. This explains why…

Selfing is unsatisfying. Selfing depends on two uncomfortable processes: grasping and loss (aka death). There is no joy in anxiously clinging to social media likes or the death of the dream of being popular. The process of selfing is a bit like licking honey from a razor: attractive at first, but unpleasant in the long run. However, there’s good news, because…

Selfing is optional! Selfing and dissatisfaction are let go of when any of the links are let go of. The simplest link to let go of is grasping. The more grasping is let go of, the more confidence arises that this letting go really does lead to well-being.

To quote the Buddha:

Whatever is not yours: let go of it.

Your letting go of it will be for your long-term happiness & benefit.2

Practice: letting go of selfing (three ways) We're going to cultivate three different ways to let go of grasping (therefore selfing & dissatisfaction). When you notice that selfing has snapped you out of the present moment, try any combination of the following: 1. Let go of thinking by turning your attention to something in your direct experience. (You can pick a meditation object out of The meditator's handbook.) 2. Let go of tensing. In my experience, mental grasping and physical tension arise together. Letting go of one automatically lets go of the other. 3. Let go of clinging. - If clinging to a possession, give something away. Practice generosity. - If clinging to a situation, try seeing it as "not personal." - If clinging to a feeling, remember: you are not that feeling. Which of these ways of letting go is the most effective for you? Do you have other ways to let go? I'd love to hear!To recap, we’ve explored how our sense of self is fabricated by our mind, and how, when unchecked, that process of selfing can lead to feelings of separation and frustration.

Having a sense of something doesn’t mean it’s there. We can have a sense of a great oak tree, reach out our hands, feel its bark, and know it for ourselves. We can also have a sense of a refreshing pond in a barren desert, reach our cupped hands into the pond, and come up empty-handed. It was just a mirage.

Is the self real and solid, like an oak tree, or elusive and unsatisfying, like a mirage?

Let’s look for ourselves.

Looking for our self

In case we haven’t met, you should know that my name is Rey. My name was Rey in July 1997, when I was freshly born and warming under the light of an incubator, and it’s Rey now. Whatever name you have, you’ve probably had it your whole life.

Names can be deceiving. It’s tempting to think that because my name has never changed, I have never changed. We tend to think that ‘Rey’ or ‘I’ (or whatever your name is) points to some part of this body-mind complex that remains the same from birth until death. From that belief in permanence follows a belief in a permanent self.

So: this permanent self … where, exactly, is it?

Is the self the body?

It’s clear that no one has the same body now that they did at birth. But the body changes over much smaller timescales, too. The health and beauty industries exist in order to cover up the wrinkles, warts, and blemishes that serve as evidence of our impermanent bodies. If we wanted to find an unchanging self, we’d have to look outside of the changing body.

Is the self the mind?

Thankfully, I have a much different mind3 from when I was born. Since then, I have learned languages, experienced countless sensations, and formed new ideas. The mind’s impermanence can be a cause for celebration.

But not necessarily. Last year, I lost my grandfather to Alzheimer’s. Watching him lose his mental faculties over the course of years made me keenly aware that the mind is not fixed. What was once gained can always be lost.

At the time, I took solace in the fact that my grandfather wasn’t himself then—that, at another point in time, he had really been him, and at that point, he wasn’t.

I don’t see it like that anymore. My grandfather’s self was not in his mind, and there is no unchanging mind that he was supposed to have possessed. His mind changed, just as all of ours do. How he was at the end of his life was not in any way fallen or inferior. It was simply how he was.

This realization has changed my relationship with my own mind. Rather than fearing losing it, I have an unshakeable conviction in using it—here, now. Knowing the mind’s impermanence, I don’t cling to a fantasy of permanence. Instead, I embrace what I’m capable of doing, and the people I’m capable of helping, with my mind in this moment.

This embrace of life feels like nothing less than liberation.

Forgetting the self

To study the buddha way is to study the self.

To study the self is to forget the self.

— Dōgen Zenji4

In summary, we’ve searched for a permanent self, but found only an impermanent mind and body. This is a pivotal moment. Are we going to run from this realization, clinging even tighter to fantasies of self and permanence? Or, just as we learned to let go of selfing, can we learn to let go of self belief?

Because we cling to belief in self as a source of security, it’s normal for letting go of this belief to be accompanied by a feeling of fear or insecurity. If we’ve structured our entire lives around our self, seeing through the illusion of that self can sometimes engender a feeling of loss or alienation. If you feel that way right now, please know that I feel for you, and I’m here if you want to talk.

At the end of the day, though, the self is, and always has been, an impossible way of existing. We’re not destroying something that is real5—we’re seeing through the illusion of something that isn’t.

The moment you learned that Santa didn’t exist, you didn’t think Santa suddenly died. Instead, Christmas functioned as before, but you saw what was happening more clearly. The same is true of the self. Everything that can be explained by the self can actually be better explained without it.

Let’s devote the rest of this essay to seeing more clearly. If we’re not fixed selves, what are we?

Introducing the person

Because it’s very easy to misinterpret teachings about not-self, let me state the obvious: You exist. No one is claiming that if you pinched yourself, it wouldn’t hurt, or that you suddenly cease to be the owner of your car.

Rather than existing permanently and independently, as selves, I’d like to propose that we exist impermanently and interdependently, as persons.

The person you were a year ago is continuous with you, but not identical to you. When a chain of dominos falls, every domino falls because of the dominos before it. In the same way, the person you are right now is continuous with the persons you were in the past. At the same time, no domino is identical to the ones before or after it. You are a different person from moment to moment.

To shift from selfhood to personhood is to abandon seeing fixed, rigid entities and instead see the world as a flow of process. (We’ll explore process more deeply in the next essay.) No behavior occurs because of fixed, essential selves—everything occurs because of flowing, impersonal processes. This means that…

Persons can change

We live in a culture that is all too happy to attribute behavior to selves. According to this logic, if I do something good, I’m essentially good; if you do something bad, you’re essentially bad. You can see how quickly extreme notions of reward and punishment follow from this view.

This is, to me, completely backwards. There are no selves to blame for human behavior. There are only processes.

If persons are processes, then when processes change, persons change. If you want to change behavior in yourself or others, don’t fabricate a sense of self around the behavior. Just investigate the processes that behavior depends on, consider your involvement in those processes, and change what you can from the place where you’re standing. That’s the most you’re capable of doing.

Reflection: seeing change in persons & processes Take a moment to center yourself. When ready, call to mind a few behaviors in yourself and others that you don't like. (This is probably not too hard!) Now, go through each behavior and ask yourself: "Have I attributed this to a fixed self, or to a changeable person?" If the former, can you cultivate a bit of acceptance for the person? (That includes you!) This behavior is not evidence of a fixed, essential self--it's the product of myriad processes. The process can change, and so can the person. Finally, consider whether you can change any of the processes on which this behavior depends. Let your mind be truly creative and flexible in imagining alternatives. How did that go for you? I'd be curious to hear!Let’s recap. We’ve explored how the sense of self is constructed by the mind, how an unchanging self cannot be found, and how we are actually changing, interdependent persons. I’ve offered practices to let go of selfing and nonjudgmentally change human behavior. I’ve alluded to how these practices enable greater freedom, connection, and happiness for yourself and others.

Now, let me lay my cards on the table: the point of these teachings is to make us more selfless.

The joy of selflessness

All the suffering there is in this world arises from wishing our self to be happy.

All the happiness there is in this world arises from wishing others to be happy.

— Śāntideva6

Have you heard of the parable of the long spoons? Put simply, it describes a world in which everyone has ample food, but whose utensils are too long to serve the food to themselves. In one scenario, the eaters try unsuccessfully to serve themselves, and starve to death. In the other scenario, they each use their spoons to feed their neighbor. Everyone is satisfied.

I’d like to suggest that we live in such a world. Consumerism magnifies our sense of separate selfhood by urging us to seek out pleasure at the expense of others. The more we grab for ourselves, the more we fear losing what we’ve grabbed. By figuratively trying to feed ourselves from a long spoon, we are starving to death.

But there’s another way. Liberated from the sense of separate selfhood, we find that our real nourishment comes from service to others—from figuratively using our spoon to help feed others. We find that unlike the false promises of pleasure, selfless behavior actually yields genuine happiness. As it happens, we also find that when we’re selfless, others are much more willing to serve and feed us in return.

When insight into not-self makes us feel severed from the world, what weaves us back into the web of life is love. In my opinion, one of the most profound teachings in Buddhism is that of the four immeasurables (brahmaviharas): four ways to relate to others from a place of selfless love, rather than selfish gain. They are:

Metta (friendliness): the wish for others to be happy

Karuna (compassion): the wish for others to be free from suffering

Mudita (sympathetic joy): celebrating the success of others

Upekkha (equanimity): treating all people equally

At first, we have strong habits of separating ourselves from others, so we explicitly practice the four immeasurables to dissolve that separation. But over time, as we perform less and less selfing, what emerges is responsiveness: an effortless, spontaneous ability to respond compassionately to the needs of others.

I’ve been pleasantly surprised by responsiveness in my own life—my ability to console someone in pain, seemingly without thought, or to come up with an on-the-fly reply to cut through tension. I think responsiveness is closely related to my essay on balance, which you can read here:

As Roshi Egyoku Nakao, former abbot of the Zen Center of Los Angeles, wrote:

The Way is revealed in the open field of relationships.

Respond without self in all situations.

If you remember nothing else from this essay, remember this quote.

Resources

My favorite book for understanding the emptiness of the self is Guy Armstrong’s Emptiness: A Practical Guide for Meditators. Armstrong greatly clarified my understanding of selfing and its relationship with the 12 links.

I also enjoyed Jay Garfield’s free series of talks promoting his book Losing Yourself: How to Be a Person Without a Self, which helped me better understand the distinction between persons and selves.

As always, feel free to comment or share!

In the next installment of The Art of Emptiness, we’re going to explore dependent origination: a way of looking at the interdependence of all things, and how that way of looking clarifies our thinking in profound ways.

Read Part 3 here:

This is a condensation of the Buddhist teaching of the 12 Links of Dependent Origination. While I won’t explain all 12 links, I will explain the last five.

By mind, I mean all subjective experience—perception, memory, thought, etc.

“Genjokoan,” trans. Robert Aitken and Kazuaki Tanahashi

I blame whoever coined the phrase ‘ego death’ for making this process seem more violent and intense than it actually is.

Bodhicaryāvatāra, trans. Padmakara Translation Group

Thans for the essays ! On this one, there's a debate within Buddhism , as I understand it, as to whether by shifting towards an idea that there is no self, but there are persons-as-processes, we're replacing belief in one thing that doesnt ultimately exist ... with another thing that doesn't ultimately exist either! Rob Burbea's more on this side of the argument, holding the mystical position that as long as we think something might be finally real, even a process, we still have further to go towards a letting go even of that. Any thoughts on that ?

Also, regarding names - I actually did change my name (both first and last) from my birth name, back when I was 31. In one sense because I felt like a different "self" (after some experiences that fit into the 270 degree area of the Buddhist circle - the paranormal stuff), but moreso to have a continual reminder of the decision I'd made regarding what would be the guiding north star for my life - similar to a new Buddhist taking precepts, I suppose.