The meditator's handbook 📓

Whether you’re a first-timer or an expert, there’s a practice for you.

Seven years ago I took my first breath.

It was in a therapist’s office on my college’s campus, where I had gone searching for help with depression and social anxiety.

When she first recommended meditation, my response was a simple no. Then it was a more verbose hell no. Why would I want to let go of thinking? Thinking had solved all of my problems so far. Surely it wasn’t the cause of them.

Somehow she convinced me. When the day came, we sat together in silence watching our in- and out-breaths for five minutes. It wasn’t long, but those five minutes of awareness showed me just how unaware my everyday existence had been, and that left me with a question — could there be more to this whole “being alive” thing?

Since then, I’ve maintained a daily meditation practice, sat with a variety of meditation groups, and attended meditation retreats of up to ten days in length. I can say definitively that the answer to my question — is there more to being alive? — is yes. Meditation has shaped my mind towards greater openness, tranquility, and compassion, and it’s awakened me to the great mystery of being alive at all.

Enough about me. Here’s where you come in.

What this article is

In this article, I share the five meditation techniques that have been the most responsible for changing my mind. They’re ordered in ascending difficulty, but I won’t stop you from jumping around. In fact, I actually encourage you to keep playing with earlier practices as you move on to later ones. Personally, I still use the first practice (metta) every single day.

Each practice comes with step-by-step instructions and a set of free resources to further your exploration. If you’re brand new to meditating, I hope this article gives you a map of the territory and enough advice to get started. If you’ve been meditating for a while, I hope this article gives you some possible next steps and resources for branching out. And if you already know everything in this article, please stop reading and come teach me!

Please email me at reymbarcelo@gmail.com with any questions you have about meditating. If I can help answer them, I will. If I can’t, I’ll find a person or resource who can.

Why meditate?

It’s the nature of the mind to wander. Mind-wandering can often be positive, but without guardrails it can turn into rumination: repeated, unhelpful thinking, usually about the self.

Meditation, at its core, is training the mind to identify when it wanders.

What makes each meditation practice unique is what you train your mind to do after you’ve noticed mind-wandering.

Each practice yields unique fruits. For example, samatha practice tends to be calming, jhāna practice can be quite energizing, and metta can yield feelings of connectedness and tenderness. (All three of these practices are explored below.)

From a Buddhist point of view, the goal of meditation is to reduce suffering. I can guarantee that, in the long run, meditation fulfills this promise. But while it can also have a host of other pleasant side effects (eg. greater productivity, success, or creativity), I recommend against expecting any of these to happen. Instead, just try to cultivate them.

Here’s a point I want to make clear: if meditation is causing you suffering, pause meditating and ask for help. While it can require effort, it should never feel painful or intense. Meditation is an act of play, experimentation, and creativity. If it doesn’t feel like that, something needs to be changed until it does.

Resources

📄 To understand the connection between mind-wandering and suffering, check out the short paper “A Wandering Mind is an Unhappy Mind.” It lives up to its title!

📄 If you encounter difficulties or you have a history of trauma, I recommend looking into trauma-informed mindfulness so you can make the practice right for you.

What all meditation practices have in common

I’m going to slightly expand on the core of meditation described above.

Commit to an object of meditation. When the mind wanders, gently bring the attention back to the chosen object. Repeat.

Emphasis on gently. Your mind is designed to wander; there’s no use in punishing it for doing its job. Instead, celebrate every time you do notice mind-wandering. You’re just cutting against the grain of human hardwiring. Casual.

The basics

Try to meditate every day, in the same time and place.1 I like to meditate just after waking up, because my mind hasn’t been destroyed from screen time yet. Your mileage may vary.

Decide in advance how long you’ll meditate for. One to five minutes is totally cool for a beginner. Just pick a length, set a timer, and try not to look at it while meditating.

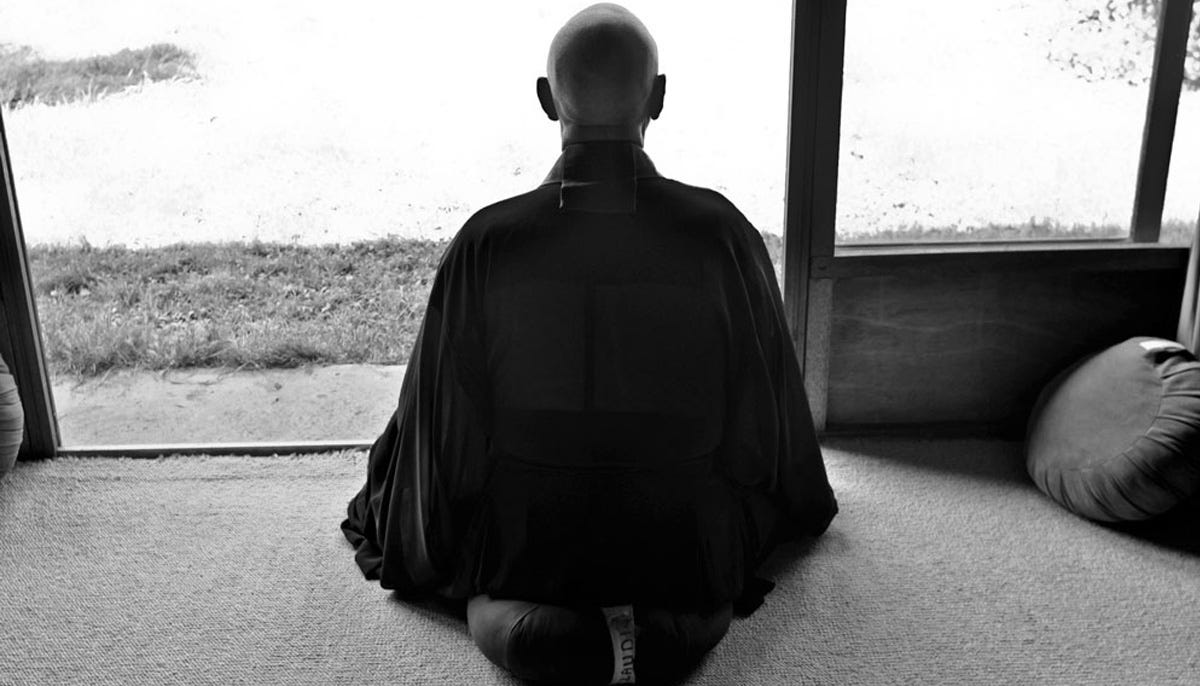

Choose a posture and move on. It’s a misconception that you can only meditate in full-lotus posture. You can meditate sitting, standing, walking, or lying down.

That said, the straighter your back, the easier things will go for you. (This is true in meditation and daily life!) Try for a posture that’s relaxed, yet alert.

Eyes are typically closed except for shikantaza. For hands, I like putting them in the cosmic mudra. If that’s not your thing, just rest them in your lap.

Identify your intention(s). For example, you might hope to relieve stress, focus better, develop better relationships, or deepen your spirituality. All are noble intentions. Remember your intention when you don’t feel like meditating. (No one feels like meditating 100% of the time.)

Use an accountability mechanism. It’s helpful to have a record of when you meditated, and for how long. That way, you can keep yourself honest and have something to look back and be proud of.

Resources

📱 My favorite free meditation app is Insight Timer (iOS, Android). You can use it as a timer, as a historical record, and as a source of guided meditations2, some of which I recommend below.

The practices

Metta

Metta is Pali3 for lovingkindness, friendliness, or goodwill. In this practice, we’ll cultivate these feelings for ourselves and others.

Most people will tell you to start with mindfulness before metta. I believe that metta is a better first practice for several reasons:

While concentration-based meditation practices take some time to yield positive results, metta feels good fast. This incentivizes you to stick with the practice in the delicate beginning.

In my opinion, if meditation is not rooted in ethics, it’s useless. You can use meditation to become a more efficient bounty hunter or multilevel marketer. I wouldn’t recommend it.

The practice

Settle into your chosen posture and see if you can generate a baseline feeling of tenderness. I like to place my hand on my heart and feel it beating for a few seconds.

Identify the person you find easiest to love at this moment. Examples include yourself, a pet, a family member, or someone who once showed you kindness.

With the person in mind, slowly repeat the following phrase: “May you be safe. May you be happy. May you be healthy. May you live with ease.”

The phrase itself is not so important. You can use a different one if you like. What we’re going for is not the words so much as a vibe of sincerely wishing for this person’s well-being.

Over time, expand the circle of well-wishing to include people you feel a little less passionately about, people you feel neutral about, and people you find challenging. Include yourself in that sequence too!

You don’t have to rush in to wishing metta for difficult people. Only expand the circle once you feel comfortable wishing metta on the current circle of people.

It’s incredibly normal to feel resistance to metta practice. I do, all the time.

There are countless reasons to resist metta, but at their root, most are saying [X] doesn’t deserve to feel good. Maybe X is you, and you think feeling good and being productive are mutually exclusive. Maybe X is someone who hurt you, and you worry that if they feel good, someone is going to get hurt. These are legitimate reasons.

When a part of you resists metta, practice metta on that part of you. The insecure part of you deserves wellbeing, as does the angry part, the shameful part, the horny part, the defensive part, etc. Wouldn’t you agree?

Resources

🔈 Try this five-minute guided metta meditation to get started.

🔈 After you’ve established a routine, you might try this fifteen-minute metta meditation from the meditation teacher Sharon Salzberg.

📄 One way to persuade yourself that metta is worthwhile is the “intelligent selfishness” argument: if we want to make ourselves feel good, the best route is actually to care for others. If only Ayn Rand knew about metta.

Samatha

Samatha (tranquility) is the practice most people in the West think of when they think about meditation or mindfulness. In it, we cultivate calmness by keeping the attention focused on a single object. For now, we’ll focus on the breath.

In spite of the popularity of the term “mindfulness,” I opted not to use it for this stage because I want to emphasize that you’ll be cultivating two skills: mindfulness and concentration. Bhante Henepola Gunaratana, the author of Mindfulness in Plain English (linked below), explains the distinction between mindfulness and concentration well:

Mindfulness is the sensitive one. He notices things.

Concentration provides the power. He keeps the attention pinned down to one item.

The practice

Settle in to your chosen posture and take three deep breaths through your nose.4 Start to notice where you feel each out-breath on the inner nostril.

Our object of meditation is going to be the sensation of the breath inside the nostrils. As you breathe in, count one. As you breathe out, count two. Continue counting with the in- and out-breath up to ten.5

Remember mind-wandering? It’s going to happen. When you notice your attention isn’t on the breath, congratulate yourself for noticing and return to counting. It doesn’t matter whether you return to one or the last number you remember.

Once you’re comfortable with counting, drop the numbers and switch to in and out.

At this point, you’ve cultivated some concentration (the energy required to return to the breath) and can start cultivating mindfulness.

Gradually expand your curiosity about how the breath feels. Is it hot, moist, tight, long? The more attention you give it, the more subtle it will appear.

When you feel confident in your mindfulness, you can drop in and out and just note the sensation itself. You don’t have to be in any rush to do this.

At this stage, we’re cultivating a mind that is calm and concentrated. Even when you’re not meditating, you can use this practice to achieve some tranquility — for example, in a stressful situation, try taking a pause and counting out a few breaths. It helps.

Resources

🔈 Try this five-minute guided mindful breathing meditation to get started.

🔈 Once you’re comfortable meditating for longer, you can try this fifteen-minute guided meditation from Tara Brach, a psychologist and meditation teacher. If you like Tara’s vibe, her podcast is also lovely.

👥 At this stage, you might find it helpful to meditate with others. Meditating in groups can help you stay committed and help resolve various pitfalls in your practice. And if you’re lucky, the people you meditate with can also become your good friends! As always, I recommend finding a group that is donation-based rather than fee-based.

📕 To learn more about the relationship between mindfulness and concentration, I highly recommend reading Mindfulness in Plain English (free PDF). It also helps bridge the gap between samatha and the next level of meditation, which is…

Vipassanā

Vipassanā is translated as insight or clear seeing. Its approach overlaps with that of samatha, but instead of training the mind to be calm, vipassanā trains it to more accurately comprehend reality.

In Buddhism, there are three marks of existence that vipassanā trains you to see clearly. Here, we are going to focus on one of them: impermanence (anicca).6

Vipassanā is a process of deconstruction. After choosing a meditation object, you will observe how the object is not stable, but a collection of constantly changing phenomena. In doing so, you will develop insight into the fundamental nature of reality — that everything is changing, all the time.

You can use anything in your direct experience as a meditation object: breath sensations, bodily sensations, or sounds, for example. In this example, we’re going to use body sensations as the meditation object.

The practice

Practice samatha on the breath until you feel sufficiently concentrated.

Now slowly scan your body, paying attention to whatever sensations you can notice.

There are many techniques for scanning the body. Some are very detailed and others are more flexible. One such roadmap is described in pages 41-43 of With Each and Every Breath (linked below). You can also search “vipassanā body scan technique” to find one that suits you.

Some sensations are pleasant. Some sensations are not pleasant. The goal is to cultivate equanimity: to refrain from grasping at pleasant sensations and to refrain from pushing away unpleasant sensations. It’s a gradual process. Be gentle with yourself.

As you attend to a given sensation, watch how it changes.

I recognize that this technique is a little underspecified. Let me give an example.

I often get headaches, which usually manifest as pressure clustered around my jawbones. Without equanimity, I label those sensations “pain,” see them as fixed, and fixate on getting rid of them.

But if I watch the sensations with equanimity, they become more fluid. The pressure may ooze down from the jawbone, or contract, or cease to be pressure at all. The headache may still be there, but vipassanā enables me to see that the nature of the headache changes from moment to moment. As a result, it becomes easier to tolerate — why obsess about changing something that is already changing without my help?

Resources

🔈 I think a good place to start is this fifteen-minute guided vipassanā meditation from Tara Brach.

📕 I like Thanissaro Bhikkhu’s With Each and Every Breath (free PDF) for advice on scanning the body and connecting breath sensation to body sensation. It also has great instructions on integrating meditation in daily life.

📺 Personally, I use the meditation teacher Rob Burbea’s “energy body” approach to scan the body. He explains his approach and offers a guided meditation in this YouTube video.

🛖 At this stage, you may benefit from going on retreat. Retreats can last anywhere from a few hours to a few weeks. I recommend S.N. Goenka’s Vipassana retreats because they’re completely donation-based and surprisingly widespread. (For transparency, I’m an alumnus of a Goenka retreat and had a great experience.)

Jhāna

Let’s revisit samatha. Recall that samatha involves concentrating on a single object. As you become more and more concentrated, you’ll encounter distinct stages of absorption that feel blissful to be in. These are the jhānas, and they can be practiced either for their own sake or as an aid to insight.

There are multiple jhānas, but here I’ll just show you how to enter the first one.

The practice

Practice samatha on an object. It can be the breath, the breath-body, or even metta. Try to become increasingly concentrated on the object.

Eventually, you’ll notice piti: a pleasant “body buzz,” usually present in the hands. Turn your attention to the piti. Practice liking the sensation without wanting it to be any different.

Concentrating on a pleasant sensation sets up a positive feedback loop, which makes the pleasant sensation even more pleasant. That means that all you should do at this point is just keep liking. You’ll know when you’ve entered the first jhāna.

If you find it hard to stay with the piti, it’s likely that wanting has crept into your practice. (This was my biggest mistake when learning the first jhāna). When you notice the wanting, try to relax the whole body and return to liking.

Once you’ve entered the jhāna, see how long you can extend it. You may pop out in a few seconds the first time; with time, you can build up to 15 minutes or more.

On leaving the jhāna, spend some time in vipassana in order to use your deep concentration to cultivate insight. Can you observe impermanence at a more subtle level than usual?

I want to be clear: jhānas are an advanced practice. Most, if not all, of them require extended time, and possibly retreat, to access. They’re not a required part of the path, and they shouldn’t be the only component of it.

Why do I recommend them, and why do I practice them? To paraphrase a climber of Mt. Everest: because they’re there.

Resources

📺 This video by Michael Taft (of the Deconstructing Yourself podcast) provides the most straightforward explanation I can find for entering the first jhāna.

📄 This chapter from Rob Burbea’s book Seeing That Frees, while not dealing with the jhānas directly, gives innumerable tips on working with concentration (samādhi). Increasing your capacity to enjoy states of concentration is the number one way to prepare to enter the jhānas.

📄 I also like this article by Substack writer Sasha Chapin that really brings the jhānas down to Earth.

Shikantaza

Shikantaza is Japanese for “just sitting.” In shikantaza, you do nothing. That’s harder than it sounds.

Zen Master Dogen described shikantaza as “all things coming and carrying out practice-enlightenment through the self.” That sounds obscure, but let me put it this way:

In shikantaza, it’s not “you” who’s meditating. Instead, everything is meditating through you.

Since that can be a little hard to grasp, the Zen meditation teacher Shinzen Young has adapted shikantaza into a style of meditation he calls “Do Nothing,” which expounds on the basic instructions.

The practice

Let whatever happens happen.

As soon as you're aware of an intention to control your attention, drop that intention.

I notice that a lot of literature on shikantaza uses phrases like drop, let go, or backward step — to me, these all connote a visceral experience of falling.

I barely understand shikantaza yet, but to me it feels like a repeated trust fall. Every time I drop my intention, what I’m really dropping is my clinging to self. There’s no meditation object to catch me; instead, I’m just held in the raw experience of the present moment. I’m obsessed with it. Your mileage may vary.

📺 Watch this video for more explanation from Shinzen Young on his Do Nothing technique.

📄 In this article, Michael Taft expands on Shinzen’s technique.

📄 If you’re really into this stuff, check out Dogen’s essay “Genjokoan,” which is dazzlingly profound and frustratingly impenetrable. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Wait, you’re still here?

So … those are the practices.

If you’ve read this far, thank you. To want to read all this, you’d have to care very deeply about me, or about yourself. Either one makes me happy.

I want to end by sharing a short anecdote about meditation’s effect on my life.

It’s a little embarrassing, but I keep a photo album called “reasons to feel good about myself.” When someone thanks me for something, I take a screenshot and put it there.

In the last two years, two things happened more or less simultaneously: 1) I started practicing meditation more seriously, and 2) the number of screenshots in “reasons to feel good about myself” exploded.

Here are a few.

You are an exceptionally kind, communicative individual with a grounded, calm, focused presence.

You leave me inspired and soothed. Really appreciate your energy and input.

You are such a wonderful listener and thoughtful friend.

It’s really, really rare for someone to care enough about me to show the kind of sincerity you did with me.

Thanks for your patience and positivity. You provided a calm, supportive environment that allowed us to continue and succeed.

Let me be clear: I never got feedback like this prior to 2022. I believe the qualities that helped each of these people were not intrinsic to me but rather the product of these practices — the very same ones I now offer to you, and which I hope yield even more positive results in your capable hands.

I hope this practice changes your life. You deserve it.

Rey ☀️

Be consistent, but also be prepared to adapt your routine if your schedule or location changes. Your meditation nook could become the baby’s nursery; your morning quiet time could become the construction crew’s drilling hour. Enter plan B.

I have mixed feelings about guided meditations. While they can be useful teaching tools for beginners, I also fear they encourage interpassivity (letting the app meditate for you). Once you’ve learned the ropes of a technique, I suggest letting go of the guided meditation and consulting a teacher if you have questions.

Pali is the language in which the words of the Buddha were first recorded.

If your nose is blocked, you can use your mouth.

The number isn’t that important. As a musician, I actually like eight better. Just don’t pick anything weird, like an odd or really high number.

The other two — unsatisfactoriness (dukkha) and non-self (anatta) — follow from impermanence.

Nice resource. Good work.

Loved this Rey and super straightforward! I will definitely refer back to this as I continue to cultivate a more joyful and easeful way of living through practicing meditation.