What is interbeing?

This way of seeing brings clarity and reduces suffering—but only if we look deeply.

Our view of the world is obstructed by a blind spot: the illusion of separateness.

This blind spot fragments our vision, causing us to misperceive everything (including ourselves) as fixed and independent. When left unexamined, this way of seeing leads to loneliness, greed, and hatred at the individual level and existentialism, war, and environmental destruction at the societal level.

Can we learn to see past the blind spot? Yes, but only with effort. Blind spots are, by definition, hard to see, and even harder to permanently unsee. Reversing the blind spot would therefore require the deliberate, and effortful, cultivation of a radically different way of seeing.

The point of this essay is to share such a way of seeing. That way of seeing is interbeing, as well as its close cousins dependent arising and emptiness. If we deliberately practice using these lenses in daily life, we can begin to let go of our blind spot and give rise to clarity, contentment, and compassion.

The question is: are we willing to look deeply enough?

Interbeing

When you look at a sheet of paper, what do you see? Perhaps you see nothing of value. Maybe you see a writing tool. You might even see a future paper airplane. If you’re the Vietnamese Zen monk Thich Nhat Hanh, you see the entire universe.

In 1987, while lecturing on his newly-coined concept of interbeing, Thich Nhat Hanh held up a paper and demonstrated:

If you are a poet, you will see clearly that there is a cloud floating in this sheet of paper. Without a cloud, there will be no rain; without rain, the trees cannot grow; and without trees, we cannot make paper.

We can say that everything is in here with this sheet of paper. You cannot point out one thing that is not here—time, space, the earth, the rain, the minerals in the soil, the sunshine, the cloud, the river, the heat. Everything co-exists with this sheet of paper.

He then declared the terms of interbeing:

“To be” is to inter-be. You cannot just be by yourself alone. You have to inter-be with every other thing.

From those seemingly simple observations — To be is to inter-be. There exists nothing which is by itself, alone — the set of profound implications is boundless.

Dependent Arising

When you look at this diagram, do you see the forest, the trees, or the roots? My answer: It depends.

Literally. The forest depends on its trees, the trees depend on their roots, and the roots depend on a network of subterranean fungi (known as the “wood wide web”) for their nutrients. None of them could exist independently.

When we look at this diagram, we can see clearly the Buddhist concept of dependent arising, which states that every thing comes into existence in dependence on other things. Everything is an interbeing.

Dependent arising is apparently simple but, upon reflection, deeply transformative. The Buddha cited it as the key insight leading to his enlightenment. I’d like to point out some of the deeper implications of dependent arising, showing how it gives rise to gratitude, a broader worldview, and well-being.

Gratitude

When we view the world like Thich Nhat Hanh, the world becomes holy. Everything depends on innumerable conditions. As a result, everything is precious.

I have a tendency to view commodities—say, a supermarket loaf of bread—as independent, fully-formed, and therefore uninteresting. When I see interbeing, I can see the mind-blowing set of conditions on which the bread depends: the ingredients that compose it, the earth in which those ingredients were grown, the labor required to grow those ingredients. In the light of interbeing, even an ordinary loaf of bread is a miracle.

Thinking in systems

When you see interbeing, your world gets a whole lot bigger. You begin to see the world not in terms of individuals, but in terms of systems. You realize that if you want something to change, don’t change individuals. Change systems.

“Change individuals” appears to be the operating principle of the internet. When someone litters, shame them. When someone acts wrongly, punish them. This battle has no end because shaming individuals for making a mistake does nothing to prevent future individuals from making the same mistake.

Changing systems requires a drastically different approach. When I see behavior I don’t like, I try to identify the conditions on which that behavior depends. Maybe that person littered because the city she lives in has underinvested in its sanitation department. Maybe that defendant grew up in a state of educational and economic deprivation; if so, I’d much rather his community be supported than he be jailed.

Dependent arising doesn’t supply easy answers, but it helps us to ask better questions. And those questions help give rise to a world where things can actually change.

The root of suffering

We all want to stop suffering. But in his quest to stop suffering, the Buddha identified the million dollar question: what does suffering depend on?

His answer can be understood on two levels. The Second Noble Truth provides the first level of understanding: suffering depends on craving. That makes intuitive sense, right? If I crave a new laptop, but I don’t have a new laptop, I’m going to suffer. The solution is pretty straightforward: to stop suffering, stop craving.

But what does craving depend on? The answer to this question, the second level of understanding, is hinted at in early Buddhism and expanded upon in Mahayana Buddhism.

Craving, and therefore suffering, is dependent on ignorance.1

Ignorance of what? Of emptiness.

Emptiness

Emptiness, or sunyata, is the central concept of Mahayana Buddhism. It’s the skeleton key that unlocks all other concepts, enables clear seeing, and ends suffering.

What is emptiness? Emptiness is a property that everything, without exception, has. When you see the emptiness of a thing clearly, you cling to it less, and therefore suffer less.

What is this property? Lack of essence.2

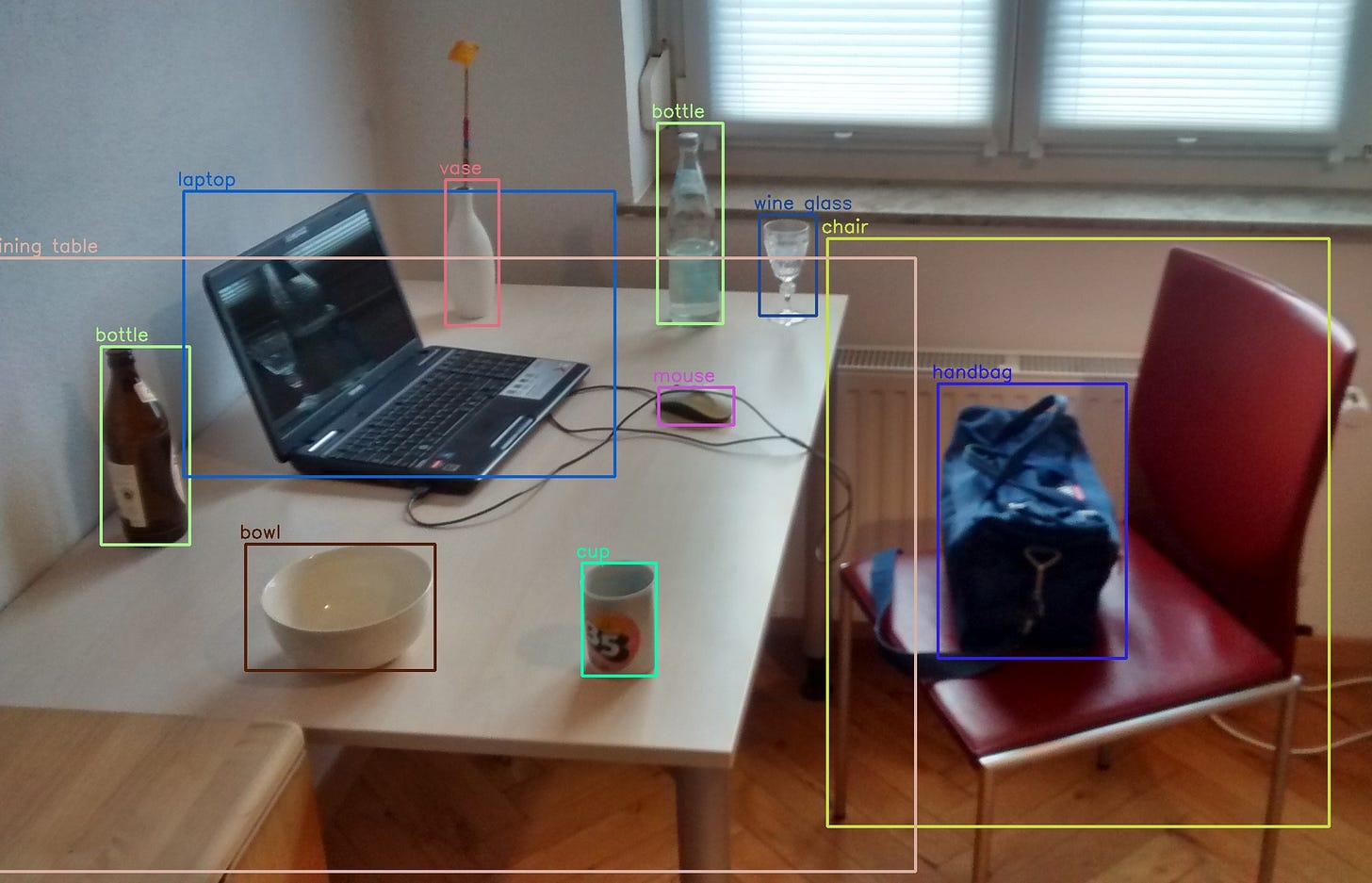

Whether we realize it or not, we see essences everywhere. When we look out at the world, we see not a unified whole, but a sea of essences. In the scene above, we see bottle-essence, bowl-essence, chair-essence, and so on.

But, as the picture might make apparent, essence is something we add to experience—it does not inhere in the things themselves. Superimposing essences onto the world comes at a cost when we confuse essences for things themselves.

Essences are independent and permanent. An essential mug, for example, depends on nothing in order to be a mug, and it will remain a mug forever. But are the things of the world really like this?

To see emptiness is to see the things of the world as lacking essence, and thereby interconnected and fleeting. As with dependent arising, this observation may seem obvious at first.

But do we really see things as interconnected? Do we really see them as ephemeral?

Let’s consider interdependence. Consider the fundamental attribution error, which states that when I make a mistake, I see my action as situational. I’m running late because of traffic. When another person makes a mistake, I assume that her action is essential. She’s running late because she’s a bad person.

If both of us lack essence, then our actions are not fundamentally who we are. They depend: on a complex web of factors, including but not limited to traffic and weather conditions. We inter-are more than we care to admit.

Do we really see things as impermanent? Let me give you a test. The last time one of your glasses broke, were you surprised?

If I’m surprised when glass shatters, then I have assumed that the glass will remain permanently intact. I have essentialized the glass. But if I can see emptiness—and therefore impermanence—clearly, I understand that the glass’s apparent wholeness is temporary. In the past it was sand, in the future it will be shards, and for the time being it takes form as a glass—just not essentially.

So, too, with life. We’re overjoyed when people assume form and shocked when they lose it—in other words, at birth and death. What if, like the glass, we could learn to see ourselves not essentially, but as appearing and empty? We could let go of anxiety about staying the same forever. (That was never a real option.) Instead, we could learn to cherish each precious moment of life even as it transforms into something new.

Compassion

We are connected as one people. If there's a child on the south side of Chicago who can't read, that matters to me, even if it's not my child. If there's a senior citizen somewhere who can't pay for her prescription and has to choose between medicine and the rent, that makes my life poorer, even if it's not my grandmother.

— Barack Obama

Now that we’ve journeyed through interbeing, dependent arising, and emptiness, the natural next question is What do I do with this?

My recommendation? Cultivate compassion.

To see interbeing is to act selflessly and to act selflessly is to see interbeing. With time, the blind spot falls away. Taking care of others becomes as natural as taking care of yourself. All care becomes self-care. All compassion becomes self-compassion. All love becomes self-love.

With gratitude to my friends and teachers Franz Manfredi, Jampa Kalsang, Guy Armstrong, Rob Burbea, and Thich Nhat Hanh, on whose insights this essay depends. Interbeing with all of you is the greatest joy.

I’m using “ignorance” to translate the Pali avijjā, also translated as delusion or confusion.

I’m using “essence” to translate the Pali svabhava, which is also translated as self-nature, inherent existence, or separate existence.